An opinion by the_corkreporter

The phrase “German Riesling” still elicits the same response from many British wine drinkers: “Isn’t that sweet?” It is a persistent fallacy that clings to out-of-date reputations and store shelves. However, the vivid, frequently bone-dry reality of what is being created and consumed in Germany today is very different from this notion.

A Legacy of a Supermarket

We must go back to the 1970s and 1980s, when mass-market German wines like Liebfraumilch, Blue Nun, and Black Tower overtook UK stores, to comprehend the origin of the myth.

In context, according to data available, these brands, which were formerly associated with sweet German wine in the UK, are still selling in significant quantities. However, the larger Liebfraumilch, Blue Nun, which sold approximately 10+ million bottles in the UK category, contributed to the development of this reputation for sweet wines but has shrunk and is no longer monitored by the general public.

These wines were designed to be approachable and reasonably priced for the British taste; they were soft, low in alcohol, and quite sweet. All three of these wines have an average price in the UK of £4.33 per 750 ml bottle. Whether or not they included a lot of Riesling, they frequently went by the Riesling name. The outcome? Drinkers in the UK were raised to associate German wine, especially Riesling, with being overly sweet and lacking in subtlety.

Supermarkets were a significant part of this story. The German wines that made their way onto British stores were nearly all of the same type: basic, cheap, and off-dry to sweet. In the meantime, mass consumers hardly ever had access to the drier and more sophisticated wines from Germany’s leading producers, which were frequently more costly and terroir-driven. A strongly ingrained stereotype was produced by this one-sided market.

In the meantime, in Germany…

Ironically, German wine production has drastically changed in the other direction, particularly since the 1990s. Nowadays, most German wines, especially Riesling, are either made dry (trocken) or with a small amount of residual sugar for balance. Dryness is the rule rather than the exception in areas like the Pfalz, Rheinhessen, and Nahe. Many producers have shifted towards a drier style, frequently producing several variations of the same vineyard location, ranging from dry to nobly sweet, even in the Mosel, where the legacy of off-dry and sweet wines is greatest.

The categorisation system for wine in Germany also changed over time. By restructuring its labelling to emphasise vineyard quality and maturity rather than sugar levels, the VDP (Verband Deutscher Prädikatsweingüter) made it easier to identify dry, terroir-driven wines. If you want a Riesling at a restaurant in Hamburg or Berlin, you’re likely to get something dry, crisp, and linear.

The Blind Spot in Britain

Why, therefore, hasn’t the Channel taken notice of this reality? Due in part to the UK supermarkets’ tardiness in catching up. Even while sommeliers and fine wine merchants are increasingly promoting dry Rieslings from prestigious German vineyards, the general public hardly ever notices these wines. For the average drinker perusing a high-street store, the image of “sweet German plonk” still looms big.

This leads to an odd cultural divide: Riesling is a national treasure in Germany, valued for its acidity, adaptability, and capacity to convey terroir in both sweet and dry ways. It’s too frequently written off as cheesy and out of date in the UK.

Dispelling the Myth

The moment has come to face the facts. By definition, German Riesling is not a sugar-coated beverage. Riesling grapes are used to make some of the most exciting dry white wines in the world, which are complex, gourmet, and age-worthy.

Wine lovers in Britain deserve better than nostalgia for the grocery store. It is the responsibility of importers, retailers, and inquisitive customers to look past the sale and learn about the true history of German Riesling. It’s mineral, racy, dry, and sure, sometimes sweet, but never dull.

Dry by Design: How a Sommelier Visionary Encouraged Wittmann, Battenfeld-Spanier, and Wagner-Stempel to Rethink German Wine

Germany has had a Riesling revolution after being written off overseas as the country of cheap bottles and sweet whites. Over the past few decades, a group of innovative winemakers from the Rheinhessen and beyond have been redefining how the world views German wine by emphasising terroir, dryness, and precision. Three names stand out as important builders of this change: Wagner-Stempel, Battenfeld-Spanier, and Wittmann. These wineries contributed to the development of the trend rather than merely following it.

From Delightful to Structurally Important

It was neither quick nor simple to switch from off-dry, mass-market wines to site-specific, dry Rieslings. However, in the late 1980s and early 1990s, a quiet revolution started in the Rheinhessen, an area that was historically most famous for Liebfraumilch. A large portion of the global market at the time still associated German wine with residual sugar. However, the potential of their vines to yield wines with depth, minerality, and ageworthiness without depending on sweetness was recognised by a new generation of winemakers.

Weingut Wittmann: The Pioneer of Organic www.wittmann.de

The Wittmann family has farmed in Westhofen since the 17th century, but Philipp Wittmann made the estate one of the greatest in the nation. Wittmann’s wines, especially those from locations like Morstein and Kirchspiel, demonstrate what dry Rheinhessen Riesling can be: structured, stony, long-lived, and profoundly site-specific. Wittmann has been entirely biodynamic since the early 2000s.

Philipp not only adopted a drier look, but he also confidently and virtuously promoted it. His Grosses Gewächs (GG) bottles are praised in both Europe and Asia and are ranked alongside the best white wines in the world.

Battenfeld-Spanier: Limestone Accuracy www.battenfeld-spanier.com

His wines, many of which come from limestone-rich soils that naturally favour slim, taut structures, have been made with surgical precision by H.O. Spanier of Battenfeld-Spanier, further south. Early on, he adopted organic and biodynamic practices, and he played a key role in expanding the possibilities for dry German Riesling.

His wines are notable for their focus, which is characterised by salt, stone, and tightly wound acidity rather than fruitiness. This is especially true of the Frauenberg and Zellerweg am Schwarzen Herrgott. Unlike the easy-drinking reputation of German white wines from the past, these wines require attention and reward patience.

Wagner-Stempel: The Relationship with Nahe www.wagner-stempel.com

Daniel Wagner of Wagner-Stempel adds a touch of a cooler environment to dry Riesling in Siefersheim, to the west. His vineyards produce wines with elevated aromatics and electrifying acidity since they are situated on volcanic porphyry soils at higher elevations. Wagner-Stempel is technically in Rheinhessen, but stylistically, it is very similar to the Nahe: exquisite tension, flavour, and clarity.

Daniel Wagner is a devoted member of the Verband Deutscher Prädikatsweingüter (VDP) and has long supported the Grosses Gewächs system. German Riesling has no singular expression, as evidenced by the elegance and force of his dry wines, particularly those from Heerkretz.

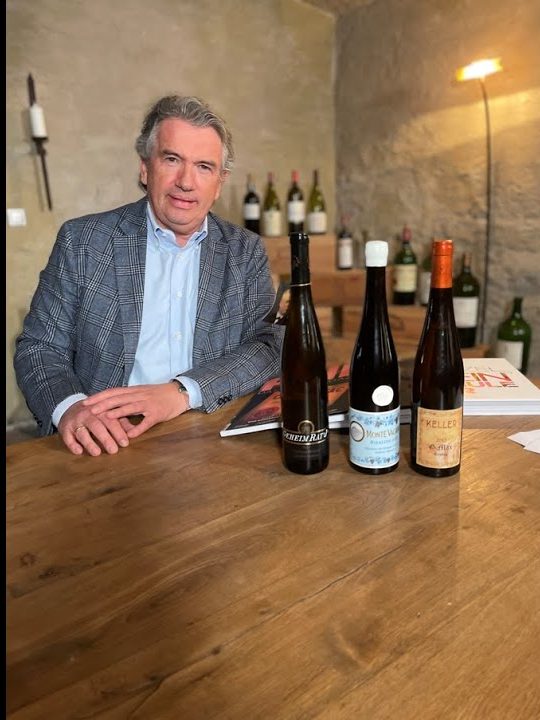

The Sommelier Who Saw It Coming: Ralf Frenzel

A new generation of sommeliers, who supported dry German wine long before the general public did, were at the forefront of this stylistic shift. One of the most important of these was Ralf Frenzel, who was sommelier at the famous Ente vom Lehel with Hans-Peter Wodarz in Wiesbaden during the time.

At a period when such selections were anything but trendy, Frenzel promoted dry, terroir-driven wines on his restaurant menus in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Before they were well-known to aficionados, he sought out producers such as Wittmann and Spanier. The foundation for a reevaluation of German wine in fine dining was established by Frenzel’s conviction that dry wines should be age-worthy and suitable for food. Through his Tre Torri Verlag, he would later have an impact on the wine publishing industry and further popularise the new wave of German vintners.

German Wine’s Dry Future – long known by Germans, the British people have to learn it!!

Dry German wines now account for the majority of domestic consumption and, to a greater extent, the export market. The world is becoming aware of the beauty, complexity, and variety of Germany’s dry whites because of producers like Wittmann, Battenfeld-Spanier, Wagner-Stempel or Ökonomierat Rebholz in the Pfalz. Their efforts pushed the VDP to redefine terroir in the German context and clarify its Grosses Gewächs system.

The fact that what was once a stylistic rebellion has evolved into the new norm, however, may be the best indication of its success. German wine is now characterised by its accuracy, clarity, and site expression rather than its sweetness. We may credit these visionaries and those who had faith in them early on for that.