By The Cork Reporter

One of the most misinterpreted aspects of wine is its sweetness. Many people associate it with sickly, inexpensive bottles from a bygone period. However, restsüße (residual sugar) is anything from straightforward in Germany, the traditional home of Riesling. It is a masterful fusion of vintage, viticultural artistry, and terroir.

It is necessary to look beyond the bottle and into the vineyard in order to fully comprehend German wine styles. Because soil and sunlight have just as big of an impact on sugar development, harvest timing, and the amount that stays in the wine as cellar choices.

The Part Restsüße Plays

The grape sugar that remains unfermented in the wine is referred to as residual sugar. Due to careful winemaking decisions, it is not artificially added in German winemaking but instead stays in the wine. A little restsüße helps balance the wine and smooth out sharp edges in cooler climates where grapes retain high levels of natural acidity.

The goal of this sweetness is harmony, not the production of dessert wines, though Germany is undoubtedly a master at those. Because of its sharp acidity, a slightly sweet Riesling often tastes drier than a fuller-bodied Chardonnay. Much of what makes German wine exciting is defined by the interaction of sugar and acid.

How Sugar Grows in the Vineyard

The vineyard is where the path to restsüße starts. Because Germany’s wine regions are some of the world’s most northern, grapes develop slowly and have to work hard to produce one gramme of sugar. Grapes can reach full maturity, which is frequently determined by must weight using the Oechsle scale, thanks to the steep, south-facing hills found in areas like the Mosel, Nahe, and Rheingau.

Slate soils predominate in places like the Mosel, where the ground retains and transmits heat long into the evening, enabling prolonged ripening. Because of this thermal advantage, vines may develop sugar more slowly while maintaining acidity, which is perfect for well-balanced, age-worthy wines.

To guarantee that sunlight reaches the grapes, the canopy above the vines is carefully controlled. In order to encourage the production of sugar without causing overripening, winemakers may deliberately thin the leaves. In addition, they frequently lower output by using green harvesting, which involves removing extra bunches of grapes early in the season to allow the remaining fruit to develop more uniformly and concentrate its sugar and flavour.

Late pruning is another crucial method in these colder areas. Growers can lessen the chance of frost damage and help vines follow a more consistent, even ripening curve throughout the growing season by postponing budburst in the spring.

Harvest is frequently a sequence of extremely selective pickings rather than a single occurrence. Early-ripening grapes for Kabinett wines may be collected on the initial pass through the vineyard. More mature fruit intended for Spätlese or Auslese may be collected at a subsequent pass. Workers may return several times to harvest just botrytised berries by hand, sometimes one at a time, in vineyards that strive for Beerenauslese or Trockenbeerenauslese.

From Grape to Glass: The Pyramid of Prädikatswein

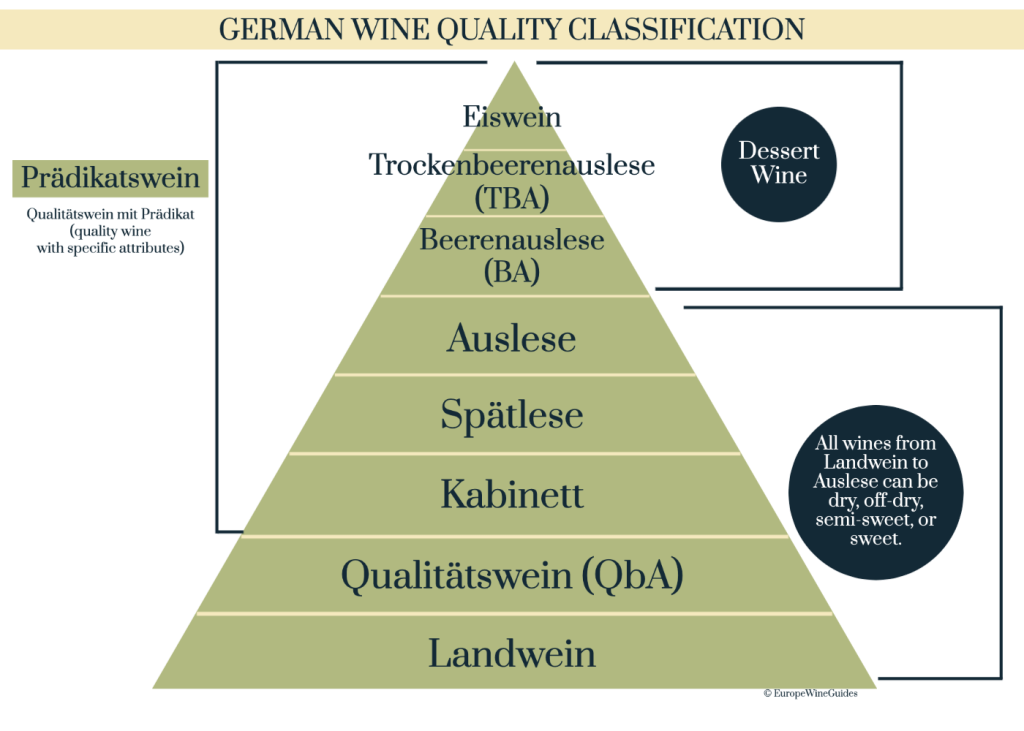

The must weight, or sugar content, of the grape juice at harvest, not the amount of sugar remaining in the finished wine, is the basis for Germany’s Prädikatswein classification system. However, this scale provides information on how vineyard choices and ripeness affect the finished product.

The grapes used to make Kabinett wines have the lowest sugar content and are usually picked early from cooler locations. They are crisp, light, and frequently have a dry flavour even when there is considerable restsüße. The term “late harvest,” or Spätlese, describes riper grapes that are harvested later in the season. These wines are more concentrated and frequently include a trace of sweetness, though many are also fermented dry.

Hand-picked bunches of exceptionally ripe grapes are used to make Auslese wines. Although there are drier varieties as well, these wines can be rich and sweet, particularly when the fruit has been impacted by botrytis (noble rot). Made from specially chosen fruit impacted by botrytis, Beerenauslese and Trockenbeerenauslese wines are among the rarest and priciest in the world. They are incredibly sweet and nectar-like.

Eiswein, on the other hand, depends on the timing of nature: When grapes are picked when frozen on the vine, their sugars and acids are concentrated into a sharply sweet yet crisp style. While Eiswein does not have the botrytised character of Beerenauslese, it does require minimum weights of at least 110 °Oechsle.

It’s crucial to keep in mind that although these divisions start with sugar content, the wine’s ultimate sweetness is determined by how much fermentation is allowed to proceed. Numerous Prädikat-level wines, especially those with the designation “trocken” (dry), are fermented almost entirely, leaving only a trace of residual sugar.

Contemporary Interpretations: Ripe Grape Dry Wines

Dry wines, particularly premium ones, have been more popular in Germany in recent decades. With its Grosses Gewächs (GG) wines, Germany’s top growers’ association, the VDP (Verband Deutscher Prädikatsweingüter), has led this initiative. Despite being created from grapes harvested at Spätlese or Auslese levels of maturity, these are invariably dry.

This method produces a bone-dry wine while showcasing the depth and complexity that ripe fruit offers. In these situations, sugar serves as a tool for increased texture, flavour complexity, and ageing potential rather than the ultimate goal.

There are plenty of dry wines, even at lower Prädikat levels. A Spätlese trocken has the body and flavour of a richer wine, but contains fewer than 9 grammes of restsüße per litre. These wines frequently have a sharp, lively flavour due to their high acidity and long hang time, with sugar acting only as a structural element rather than as tongue sweetness.

A Sweetness Not Added, Earned

German wine is exceptional due to its accuracy as well as its range of sweetness. The use of restsüße is never random. Site, vintage conditions, and the grape’s inherent character all play a role in the decision. That hint of sweetness is often the product of hard work—hand-climbing steep hillsides, carefully pruning and training plants, and harvesting grapes in waves to attain the ideal balance.

The more insightful inquiry is not whether a German wine is sweet, but rather how that sweetness functions inside the wine. Is it creating a bridge to minerality, highlighting the fruit, or bringing out the acidity? Sugar is a structural and aesthetic choice that is woven into the fabric of the finest wines in Germany; it is neither a fault to be hidden nor a marketing gimmick.

In summary, “Restsüße” is a signature rather than a shortcut.

The German approach to sugar is closely linked to vineyard culture and history, ranging from the golden opulence of a Trockenbeerenauslese to the featherweight appeal of an early-picked Mosel Kabinett. Each drop of restsüße reveals information on harvest timing, botrytis development, trimming choices, and sun exposure.

German wines serve as a reminder that, in a society that is frequently fixated on using the term “dry” as a mark of seriousness, sweetness can be just as noble—and occasionally even more so—when applied with skill and intention.