Today, it sounds like a humorous anecdote from times long past, but just 100 years ago, there was a tiny state with the curious name “Free State Bottleneck”. This peculiar microstate was founded in the turmoil of the post-war period of the First World War and only survived for a few years, from January 10, 1919, to February 25, 1923. In this blog article, we will examine the fascinating history of this microstate and the circumstances of its founding as well as its brief, but take a closer look at its exciting existence.

The emergence of the Free State of Bottleneck

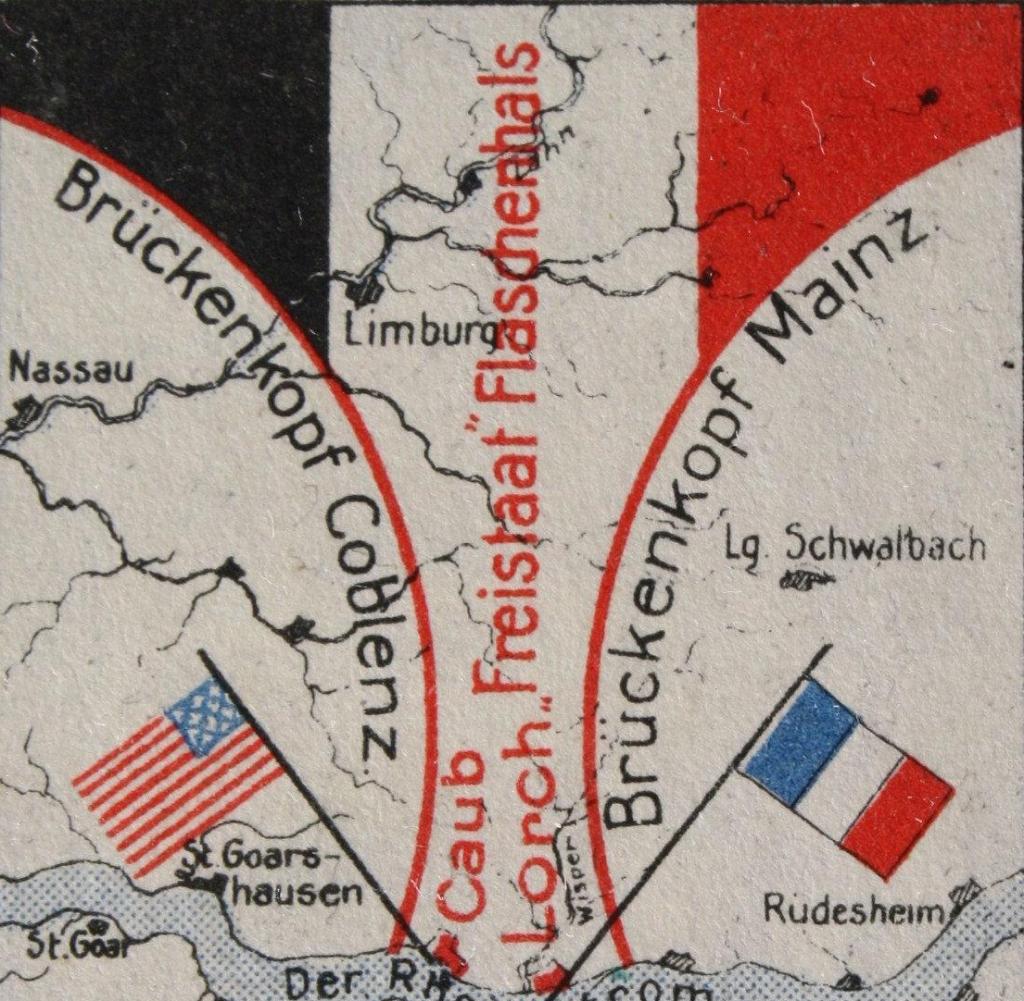

After the end of the First World War, the western provinces of Germany were occupied by the Allied armies. In order to maintain a military presence east of the Rhine, the victorious powers established semicircular bridgeheads with a radius of 30 kilometres near Cologne, Koblenz and Mainz. The Mainz bridgeheads were controlled by French troops, while American troops occupied Koblenz. These two bridgeheads touched at Laufenselden im Taunus, not overlapping but leaving a free space between them—an unoccupied area in the shape of a bottleneck. This narrow strip of land soon became the “Bottleneck Free State”, a tiny independent state cut off from the outside world and separated from Germany, known at the time as the “Weimar Republic”.

The administration of the Free State was organized by none other than the mayor of Lorch, Pnischeck. He also introduced his own currency, “Free State Money”, which is now extremely popular with collectors. The emergency banknotes were printed with sayings that reflected the mood of the Free State residents at the time and, at the same time, humorously illustrated the state’s special situation.

Some of the sayings on the emergency banknotes were:

“Nowhere is it more beautiful than in the Free State of Bottleneck.”

“In Lorch on the Rhine, the cup rings, because Lorcher wine is a worry-breaker.”

“When Franzmann moved to the Rhine, a lot of rock fell from the Nollig” (a reference to the Lorch landslide).

“If Adam Lorcher had had wine, he would not have eaten the apple; this vine juice would have made him deaf, contrary to Eve’s cunning.”

Challenges of the Free State Bottleneck

The Free State of Bottleneck was known not only for its curious origins and its idiosyncratic currency but also for the challenges that its residents had to overcome. With a population of around 8,000 people in the towns of Lorch and Kaub as well as the communities of Lorchhausen, Sauerthal, Ransel, Wollmerschied, Welterod, Zorn, Strüth and Egenroth, supply was extremely difficult.

There were no road connections to unoccupied Germany, meaning that all goods and postal traffic took place on smuggling routes. The use of railways came to a complete standstill as no trains were allowed to stop in the Free State. A notable exception was a freight train carrying French coal from the Ruhr area, which was parked at the Rüdesheim train station. A brave train driver from the Free State hijacked the train and brought the coveted heating material back to the “bottleneck”, where it was distributed among the population.

Smuggling traffic also flourished across the Rhine at night and in fog. Courageous residents of the Free State used ox carts to smuggle wine from the occupied Rheingau along forest paths and to keep it out of French hands. Storage in the cellars of Lorch and Kaub helped improve the wines and made them so sought-after that they still fetch high prices at auctions today.

The end of the Free State bottleneck

On February 25, 1923, the Free State of Bottleneck was occupied by French troops, contrary to the agreements of the Treaty of Versailles. But the occupation was only short-lived because, on November 16, 1924, the French troops withdrew again and gave up the Free State of Bottleneck.

Freistaat Flaschenhals GbR

Inhaber: Peter Josef Bahles

Bahnstraße 10

56349 Kaub

06774 918064

info@freistaatflaschenhals․de