The Comunidad de Madrid is often celebrated for its grand boulevards, Baroque palaces, and bustling tapas bars—but beyond the reach of its vibrant city life, a parallel world of vineyards stretches across rolling hills, riverbanks, and ancient plains. This is the land of Vinos de Madrid, a Denominación de Origen Protegida (D.O.P.) that bridges modern urban identity with a deep-rooted rural heritage. To travel through this region from its northernmost vineyards to its southern extremes is to explore a mosaic of soils, altitudes, grape varieties, and philosophies that together form one of Spain’s most surprising and dynamic wine territories.

A Brief History of Madrid’s Wine Legacy

Viticulture in Madrid has ancient roots. Archaeological finds point to vine cultivation as early as Roman times, particularly around Titulcia and Complutum (modern Alcalá de Henares). During the Middle Ages, monastic communities preserved viticultural traditions, while the 16th and 17th centuries saw wine from Navalcarnero and Arganda flow into Madrid to slake the thirst of royals, clergy, and commoners alike. Navalcarnero, in particular, gained renown for its garnet-red wines and rustic cellars carved into sandstone. Over centuries, this trade shaped the capital’s relationship with its surrounding rural belt, turning wine into both a necessity and a symbol of local pride.

By the 19th century, Madrid’s vineyards faced the same trials as elsewhere in Europe: phylloxera, urban sprawl, and industrialisation. But resilience won out. By 1990, the creation of the Vinos de Madrid D.O.P. marked a rebirth—uniting three main subzones (San Martín de Valdeiglesias, Navalcarnero, and Arganda) under one official recognition. Today, the D.O.P. stretches across more than 60 municipalities and nearly 9,000 hectares of registered vineyards, with a growing reputation for quality, sustainability, and stylistic diversity.

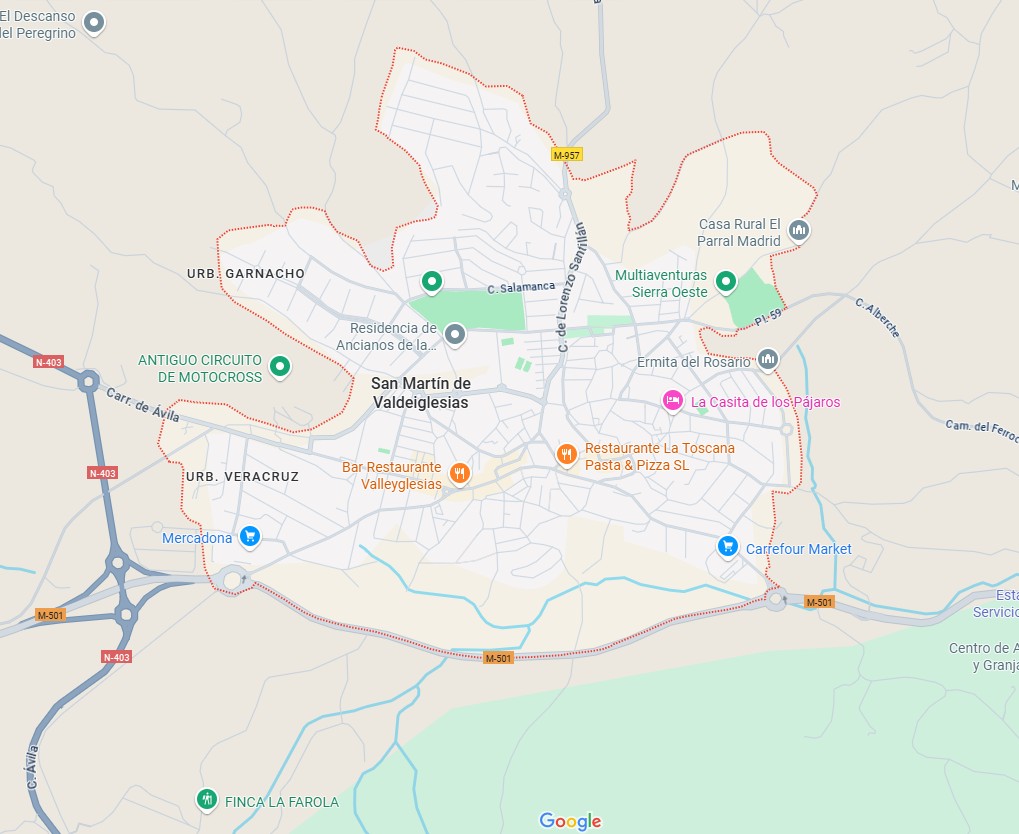

Northern Highlands: San Martín de Valdeiglesias

Our journey begins in the Sierra de Gredos foothills, where ancient mountain ranges cast their cooling influence over the vineyards of San Martín de Valdeiglesias. This is the wildest and most topographically rugged of the three subzones. Altitudes soar beyond 800 metres, and the climate is definitively continental with a pronounced alpine influence—winters are long and harsh, summers dry and sunny, and the nights always cool.

The soils here are predominantly decomposed granite, a light, acidic substrate that drains freely and retains minimal organic matter. These conditions result in low yields and high concentration, especially in old-vine Garnacha, the star of the region. These Garnachas are fine-boned, floral, and fragrant—worlds away from the jammy style found elsewhere in Spain. The granite lends a whisper of salinity and minerality, while the cool climate extends ripening and preserves acidity.

Many vineyards are bush-trained and over 50 years old—some exceeding 80 years—which further concentrates fruit and deepens expression. Albillo Real, a local white variety, also finds its ideal home here. Grown on the higher slopes, it produces textured, waxy wines with notes of orchard fruit and wild herbs, often aged in large oak or concrete eggs to highlight its broad mid-palate and subtle floral character.

While Syrah and Moscatel de Grano Menudo have been experimentally planted in some sites, Garnacha and Albillo remain the soul of San Martín. Wines here are typically fermented with native yeasts and see minimal new oak, reflecting a low-intervention ethos championed by producers like Bodega Marañones, Comando G, Las Moradas, and Bernabeleva. Biodynamic and organic farming are becoming increasingly common, especially in granite-heavy zones like Rozas de Puerto Real, Cadalso de los Vidrios, and Pelayos de la Presa.

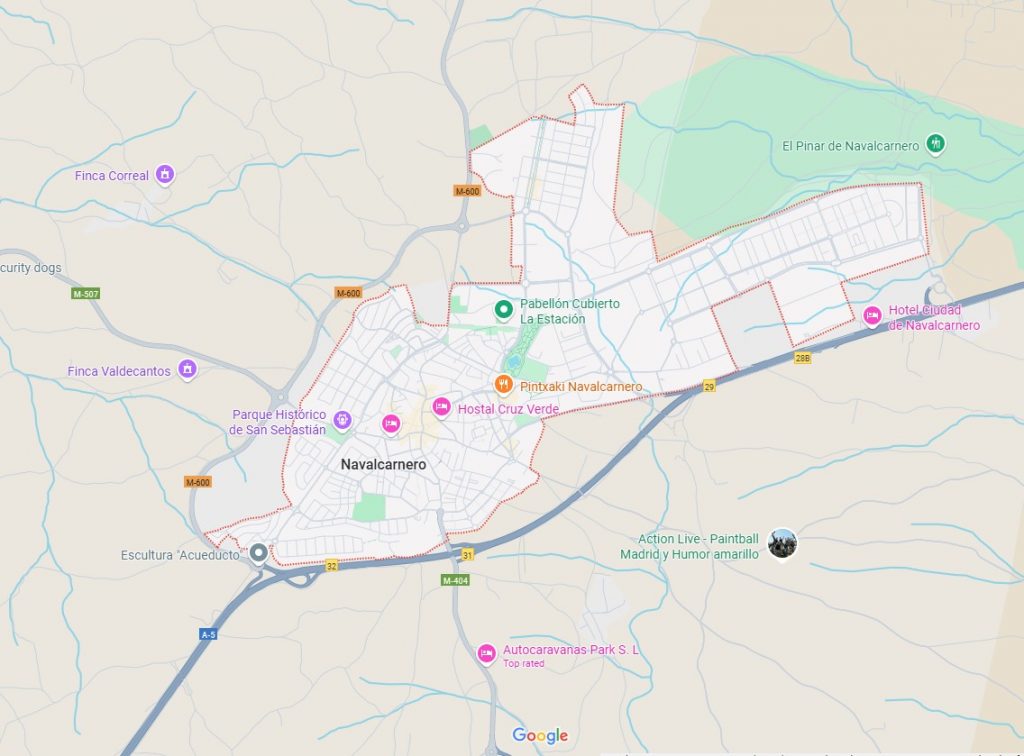

Central Transition: Navalcarnero

As we descend toward Navalcarnero, the highland contours mellow into gentle plateaus and low rolling hills. The altitude drops slightly to around 600–700 meters, and the soils begin to shift. Here, we find a mosaic of sandy clay, silt, and calcareous loam—less acidic than granite, more structured, and better at water retention. The vineyards are more exposed to Mediterranean influences, especially from the southwest, where warm air currents moderate the cooler Gredos breeze.

This shift in climate and soil supports a wider range of varieties. Garnacha continues to dominate the reds, though it takes on a riper, rounder profile than its Gredos sibling—more strawberry and ripe cherry than herbs and spice. Tempranillo has made significant inroads here, often blended with Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, and Syrah to create structured, fuller-bodied wines with ageing potential. The white grape Malvar, once relegated to mass production, is being reinterpreted by a new generation of winemakers who use skin contact, lees ageing, and barrel fermentation to explore its subtle aromatic range and refreshing acidity.

Vineyards in towns like Villamanta, Sevilla la Nueva, and Navalcarnero itself are often decades old, planted on gently sloping parcels that absorb ample sunlight. This central zone is also home to some of the region’s most historic underground cellars—many carved into the clay and sandstone beneath town squares, a legacy of 17th-century civic winemaking.

Producers like Bodegas Andrés Morate, Bodegas Licinia, and Vinos Jeromín lead the movement toward organic certification, while others like Pedro García and Casa Marqués experiment with amphorae, wild fermentations, and creative blends. This middle zone acts as a bridge—stylistically, climatically, and geologically—between the extremes of San Martín and Arganda.

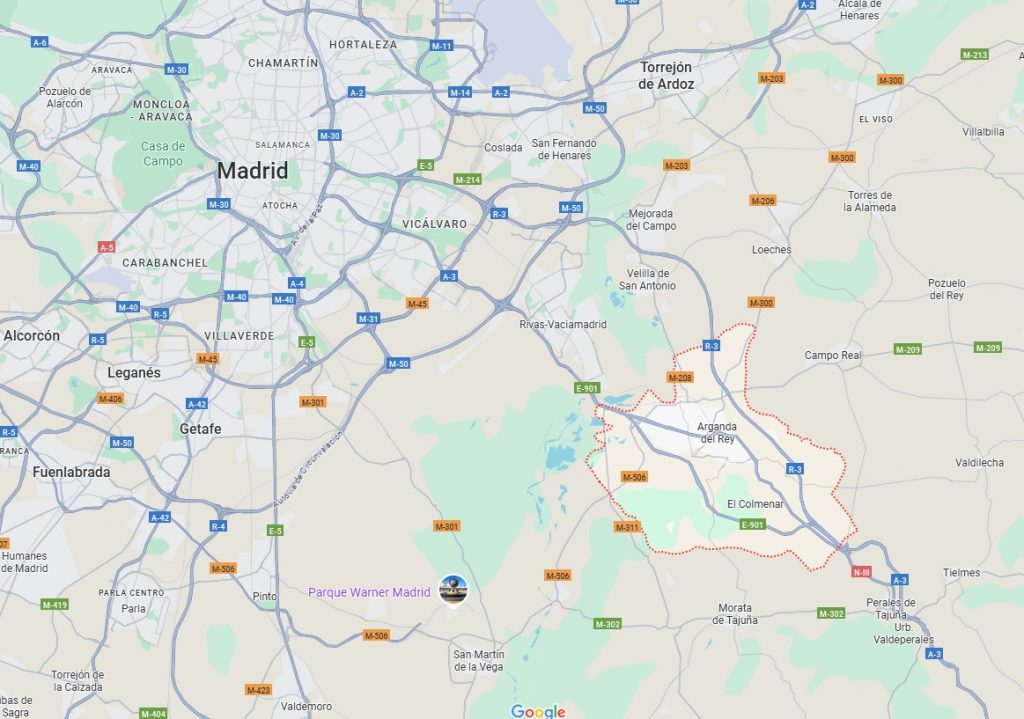

Southern Plains: Arganda

South of the Manzanares River, the landscape opens wide. Arganda is the largest and most productive of the three subzones, accounting for nearly 50% of the D.O.P.’s surface area. The terrain here is flatter, sun-drenched, and arid, but broken up by the river valleys of the Tajuña, Jarama, and Henares, where cool morning fogs help to regulate temperature and delay ripening.

The soils here are more varied than elsewhere in the D.O.P.—a combination of clay-limestone, gravel, chalky loam, and river alluvium. In particular, the presence of calcareous clay contributes to the firm structure and longevity of Tempranillo, which flourishes under these conditions. The region also produces expressive Syrah, Cabernet Sauvignon, and Petit Verdot, often in international-style blends aged in new French and American oak.

Malvar, the historic white grape of Madrid, reaches its full expression here. In its best iterations, it offers herbal, citrusy wines with a saline edge—particularly when grown in limestone-heavy plots near Valdilecha and Arganda del Rey. Some producers are even reviving Airén, often dismissed elsewhere, but now being reimagined as a neutral canvas for terroir-driven whites.

Vineyards here are larger and more mechanised, though a growing movement of small-scale producers is adopting sustainable and organic practices. Bodegas Tagonius and Viñedos Gosálbez-Orti are known for precision viticulture and minimal intervention. Bodegas Peral and Muñoz Martín preserve old bush vines on limestone terraces, while Laguna, Sanz La Capital, and Viña Bardela use oak and concrete to create age-worthy reds that rival those of Rioja or Ribera del Duero.

Grapes Across the D.O.P.

Across the three subzones, over 30 grape varieties are authorised, though a few dominate.

For reds, Garnacha, Tempranillo, Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, and Syrah are most common, with a growing presence of Petit Verdot and Graciano. Old-vine Garnacha is the region’s crown jewel, producing wines that range from lithe and mineral to bold and structured, depending on soil and elevation.

For whites, Malvar and Albillo Real are the key native varieties. Malvar brings zesty acidity and herbal lift, while Albillo Real is round, textural, and often suited for oak or skin-contact winemaking. Moscatel de Grano Menudo, Airén, and Viura are also planted, though in smaller quantities.

Increasingly, growers are focusing on site-specific plantings, matching grape to soil with greater precision. Garnacha on granite, Tempranillo on clay-limestone, Albillo Real on sandy hillsides—this terroir-driven approach is reshaping Madrid’s wine identity.

From Capital to Countryside: Madrid’s Wine Identity

What unites this diverse region is not uniformity, but contrast—high-altitude granite terraces, river valley loams, and sun-drenched plains all coexist within an hour’s drive of the Spanish capital. Vinos de Madrid is both deeply local and inherently cosmopolitan. Its growers and winemakers are increasingly embracing sustainability, organic farming, and low-intervention methods. Tradition is honored—often in the preservation of old bush vines and native grapes like Malvar or Albillo Real—but not at the expense of innovation.

Throughout the region, there’s a palpable pride in elevating wines once relegated to bulk production. Whether it’s a sleek Garnacha from San Martín, a structured Tempranillo from Arganda, or a saline Malvar from Navalcarnero, Madrid’s wines now speak with clarity, purpose, and originality.

As the sun sets over the southern plains and the towers of Madrid glint in the distance, one realizes this is a region in motion—not just geographically, but culturally and stylistically. Vinos de Madrid is more than a wine region; it’s a statement of identity, proof that proximity to a metropolis need not dilute rural authenticity. If anything, it sharpens it.