Chablis Grand Cru holds a revered position among wine enthusiasts and professionals worldwide. Nestled on the right bank of the Serein River in northern Burgundy, this small collection of vineyards produces Chardonnay wines that stand apart for their piercing acidity, flinty minerality, and exceptional ability to age. Yet the true source of their identity lies beneath the vines themselves. In Chablis, soil is not just the ground upon which vines grow—it is the foundation of the wines’ character, complexity, and refinement.

The soils of Chablis Grand Cru are a fascinating mosaic of limestone, clay, and marl. Each element plays a defining role in vine development and the resulting wine style. To understand the unique nature of these wines, one must look deep into the earth that sustains them.

At the heart of Chablis Grand Cru lies the legendary Kimmeridgian marl. This soil, formed over 150 million years ago, is a blend of clay and limestone layered with fossilized marine life, particularly small oysters known as exogyra virgula. The limestone content ensures excellent drainage, compelling the vines to dig deep for moisture and nutrients. This deep rooting limits yields and concentrates flavors in the grapes, factors that are essential for producing high-quality, expressive wines. The clay component of Kimmeridgian marl, meanwhile, retains enough moisture to nourish the vines during dry spells, helping maintain balanced vine health.

This unique soil is the main reason behind Chablis’ celebrated minerality. The wines exude notes often described as flinty, chalky, or saline, giving them a precise and structured character. Combined with the region’s cool climate, Kimmeridgian marl endows Chablis Grand Cru wines with taut acidity and an unmistakable sense of place.

Though Kimmeridgian marl dominates the Grand Cru vineyards, areas of Portlandian limestone do appear, especially on upper slopes and vineyard margins. Portlandian limestone is younger and denser than Kimmeridgian marl, and its compact structure promotes rapid drainage. Vines growing in these areas are more prone to water stress during warm seasons, which leads to smaller berries and lower yields. However, this also results in concentrated flavors and vibrant freshness. Wines influenced by Portlandian limestone tend to be slightly lighter in structure, with an emphasis on citrus and floral notes rather than the deep, stony minerality typical of Kimmeridgian soils.

Clay, often overlooked in discussions of Chablis’ geology, plays a critical supporting role. Found in layers within the marl and limestone, clay retains water and ensures a steady supply to the vines throughout the growing season. Where clay is more abundant, the wines tend to develop a rounder, softer texture, balancing the razor-sharp acidity and adding a subtle richness to the palate. While clay may not dominate the personality of Chablis wines, it helps moderate the extremes and contributes to their harmony.

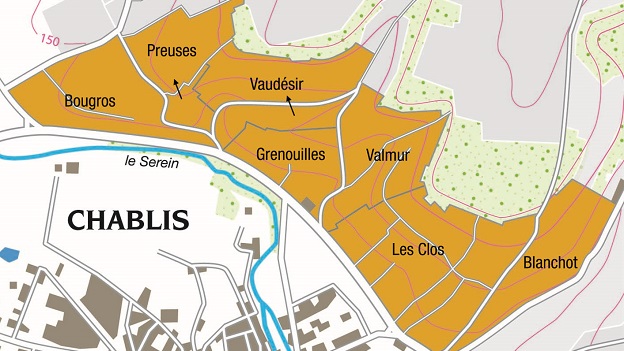

The most fascinating aspect of Chablis Grand Cru, however, lies in how these soils manifest differently across each of its seven vineyards. Though all share the same geological origin, subtle variations in soil depth, slope, and exposure create distinct expressions of Chardonnay.

Les Clos is perhaps the most renowned and powerful of the Grand Crus. Its steep slopes, covered in shallow, stony soils rich in limestone, produce wines that are structured, intense, and built to age. The wines from Les Clos often show pronounced flinty minerality, concentrated citrus fruit, and a long, complex finish. They are frequently described as the most complete and classic expression of Chablis Grand Cru.

In contrast, Vaudésir occupies a more sheltered amphitheater-like site, where marl soils are softer and pockets of clay are more prevalent. The wines of Vaudésir are generally more aromatic and supple than those of Les Clos, offering delicate floral tones, a rounded palate, and an elegance that makes them particularly appealing in their youth.

Valmur, located in a small enclosed valley, is characterized by a cooler microclimate and a mixture of marl and clay soils. The wines from Valmur are typically taut and mineral-driven, with firm acidity and a leaner, more austere structure when young. Over time, these wines develop graceful complexity, offering a more restrained yet precise expression of Chablis.

Blanchot presents a subtler side of Chablis Grand Cru. Its east-facing exposure and slightly higher proportion of Portlandian limestone result in a cooler growing site. Wines from Blanchot are known for their finesse and understated charm. Rather than bold minerality, they display delicate floral aromas, bright citrus notes, and an elegant, refined texture.

Bougros, situated closer to the Serein River, benefits from deeper clay soils, which lend richness and body to the wines. Bougros produces some of the broadest and most generous wines among the Grand Crus. They are often rounder and slightly softer in acidity, delivering immediate charm and lush fruit, though they still retain the essential Chablis freshness.

Preuses, perched on thin soils over hard limestone, is celebrated for producing some of the most graceful and delicate wines of the region. Excellent drainage encourages vine struggle, leading to wines that are bright and floral, often with a distinct saline note that adds tension and complexity. Preuses is considered by many as the most elegant of the Grand Cru vineyards.

Grenouilles, the smallest of the Grand Cru vineyards, combines marl and clay soils with a favorable south-facing slope. This combination yields wines that strike a harmonious balance between richness and freshness. Grenouilles wines are often aromatic and expressive, with softer acidity and a more charming, approachable character compared to the more austere Grands Crus like Valmur or Les Clos.

In Chablis Grand Cru, soil is not a static element but a dynamic force shaping every aspect of the wine. From the fossil-rich Kimmeridgian marl to the dense Portlandian limestone and water-retentive clay, each component contributes to vine health, grape composition, and ultimately, wine character. The seven Grand Cru vineyards, sharing a common geological ancestry, express this terroir in unique and captivating ways.

For sommeliers, wine professionals, and passionate enthusiasts alike, understanding the soils of Chablis Grand Cru is essential to appreciating the complexity and diversity of these iconic wines. Beneath every sip lies a story written over millions of years, a narrative of ancient seas, buried fossils, and the slow work of time itself. To drink Chablis Grand Cru is not just to taste Chardonnay, but to experience the essence of the land from which it came.