There are vineyards in Burgundy that announce themselves with the confidence of centuries-old acclaim, and there are others that whisper—softly, steadily—yet with a persistence that can never be ignored. Clos de la Maréchale in Premeaux truly belongs to the latter category, a vineyard whose understated power reveals itself not in ostentation but in endurance. To write about it is to walk a thin line between history and geology, memory and instinct. But perhaps that is precisely what makes this parcel so compelling: it resists simplification. It requires time, attention, and a willingness to understand Burgundy not only through its grands crus, but through the vineyards that quietly sculpt its identity.

A Name from a Forgotten Chapter

The name Clos de la Maréchale immediately evokes an almost feudal grandeur. Its origins trace back to the 18th century, when the land belonged to a military family whose most prominent member was a Maréchal de France—one of the highest ranks in the royal armed forces. While the precise individual is a matter of local debate, the title alone was enough to cement the vineyard’s cultural identity in the region. Burgundian place names often tie land to memory, and here the echo of military honour survives long after the lineage has faded.

Throughout the 19th century, the vineyard changed hands in a pattern typical of post-Revolution Burgundy. The fragmentation of land ownership, the persistent reorganisation of estates, and the political convulsions of the period all contributed to the shape we recognise today. Yet Clos de la Maréchale remained relatively intact compared to neighbouring parcels. The Mugnier family acquired it in 1902, weaving the vineyard into the lineage of one of the most respected wine families in the Côte d’Or.

Clos de la Maréchale itself is a single vineyard (monopole) owned entirely by Domaine Jacques-Frédéric Mugnier. It does not consist of three separate named vineyards in the Burgundy appellation sense — it is one contiguous clos.

However, in historical cadastral terms and vineyard mapping, the Clos de la Maréchale estate is registered in multiple cadastral plots rather than being one single parcel on the land registry. According to detailed historical analysis, the clos comprises:

- A main vineyard plot (cadastre no. 1, ~9.6251 hectares),

- A small plot used for the building at the top of the clos (cadastre no. 2, ~0.0753 hectares),

- And a third small cadastre plot outside the wall (cadastre no. 3, ~0.1686 hectares) that is historically associated with the vineyard.

These cadastral divisions are administrative land units and not independent vineyard identities — they are all part of the single Clos de la Maréchale vineyard on the ground. Most maps and producers treat the entire area as one single premier cru clos.

Additionally, when Domaine Mugnier makes more than one wine from this site, they sometimes use the historical name Clos des Fourches for a secondary cuvée from younger vines within the same clos, but this is a winemaking designation rather than a separate vineyard.

Those early decades under Mugnier stewardship reflect an era when viticulture was almost stubbornly traditional. Horse-drawn ploughs carved the rows, treatments were limited and often rudimentary, and the rhythm of the vineyard was governed less by technology than by observation. The 20th century would bring upheaval—phylloxera before the family took ownership, two world wars, depopulation of the countryside, and the shift toward chemical farming in the post-war period—but the Clos weathered them all. Even during the decades when the vineyard was leased to Domaine Faiveley (from 1950 to 2003), its identity remained unmistakably tied to Premeaux’s calm, southern spirit.

A Vineyard at the Threshold of the Côte de Nuits

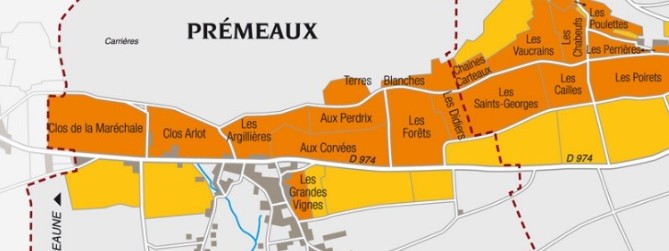

Geographically, Clos de la Maréchale occupies a threshold position—one foot in the muscular identity of Nuits-Saint-Georges, the other leaning toward the subtlety of the Côte de Beaune. Situated in Premeaux-Prissey, technically within the Nuits-Saint-Georges AOC but often stylistically distinct, the vineyard lies at the southernmost extension of the Côte de Nuits. It is a place where borders blur: a climatic hinge, a geological seam.

The parcel itself is large by Burgundian standards, stretching across approximately 9 hectares. This scale allows for microvariations seldom seen within single lieux-dits. The upper slopes sit on compacted limestone from the Jurassic era—hard, bright, fractured rock that drains quickly and forces the vines to struggle, producing berries of small size and intense concentration. Lower down, the limestone becomes interlaced with richer clay and pockets of silt, remnants of ancient alluvial movements that left behind deeper, cooler soils.

Over millions of years, geological uplift and erosion created the undulating patina of soils we see today. While not as fractured or dramatic as the slope profiles of Vosne or Gevrey, Premeaux possesses its own quiet eccentricities. A thin band of marl cuts horizontally across the vineyard, offering a distinct textural element expressed subtly in the wine’s structural frame. The entire clos faces east-southeast, absorbing gentle morning light and avoiding the harsher western heat—an orientation that was once a mere observational detail but is now, in a warming climate, a saving grace.

The altitude varies subtly, from roughly 240 to 260 metres. This may sound insignificant on paper, yet such gradations in Burgundy produce perceptible shifts: cooler air drainage from the Combe, greater diurnal variation, and a slight difference in ripening curves. All of these lend Clos de la Maréchale a natural equilibrium that feels increasingly rare.

Viticulture in Dialogue with Time

Historically, the vineyard was planted—like much of Nuits-Saint-Georges—with Pinot Noir. The choice was pragmatic, cultural, and climatological: Premeaux’s soils, exposure, and natural tannic architecture suit the grape with almost poetic inevitability. But what truly defines the site is the evolution of viticulture across generations.

During the Faiveley lease period, vineyard management reflected the era’s priorities: yield control, chemical treatments when necessary, and a practical rather than philosophical approach. The wines were structured, often stern in youth, sometimes marked by the assertive extraction characteristic of Faiveley in the late 20th century.

When Frédéric Mugnier resumed full control in 2004, the shift was immediate and profound. His philosophy—gentle, precise, deeply attentive—transformed the narrative of the vineyard. He reduced yields, embraced sustainable viticulture, and focused on allowing the vineyard’s natural temperament to re-emerge. Mugnier’s approach is famously minimalist, yet it is grounded in meticulous detail rather than laissez-faire romanticism. His work in Clos de la Maréchale represents a re-centering of the vineyard’s identity: more voice, less makeup.

Winemaking here leans toward infusion rather than extraction. Whole-cluster use varies depending on vintage expression rather than ideology. Fermentations are slow and measured, extractions are soft, and oak influence remains discreet. The goal is not to impose a house style but to transmit the vineyard’s quiet power with fidelity.

Other domaines have shaped the vineyard’s historical reputation, particularly during the lease, but it is Mugnier who ultimately defines how the world understands Clos de la Maréchale today.

The Vineyard’s Place in Local and Burgundy Culture

Within Premeaux itself, Clos de la Maréchale has long carried a certain symbolic weight. It is the largest monopole in the Côte de Nuits, giving it immediate cultural and economic significance. Its presence anchors the southern edge of Nuits-Saint-Georges, creating a kind of viticultural punctuation mark. Locals often refer to it simply as “La Maréchale,” not out of laziness but familiarity. It is woven into the identity of the village.

Economically, the vineyard has played a stabilising role for more than a century. During the Faiveley era, it contributed to the domaine’s strong holdings in the Côte de Nuits, while for Mugnier today it offers a counterpoint to the ethereal styles of Chambolle-Musigny. The wines have become essential to Burgundy collectors—valued for their consistency, their age-worthiness, and their ability to express a côté of Nuits that is both structured and serene.

Pricing has risen steadily over the past two decades, though still modest compared to the grands crus to the north. Its collectability has grown not merely because of scarcity—monopole wines always invite that kind of attention—but because Clos de la Maréchale occupies a sweet spot in Burgundy’s psychological landscape: it is prestigious without being ostentatious, complex without being obscure, expressive without being flamboyant.

In many ways, it exemplifies Burgundy’s enduring tension between humility and renown.

Why Clos de la Maréchale Matters Today

In the contemporary moment, when climate change, land speculation, and generational transitions define much of the Burgundian conversation, Clos de la Maréchale serves as a quietly persuasive case study.

Its orientation and altitude protect it from the extremes that plague warmer vintages. The deep-rooted old vines—some over 60 years old—navigate periods of drought with surprising resilience. Mugnier’s restrained approach avoids over-ripeness, maintaining a nervy freshness that has become increasingly rare.

The vineyard also reminds us that Burgundy’s story is not solely written in grand crus. Much of the region’s identity—historically, culturally, and economically—resides in lieux-dits like this one, whose character enriches the greater mosaic of the Côte d’Or.

Generationally, Mugnier himself represents continuity without stagnation. His work is informed by the past but not shackled by it. His interpretation of Clos de la Maréchale has redefined its place on the global stage, demonstrating how a vineyard that was once overshadowed by more famous names can, with thoughtful stewardship, become one of the most intellectually compelling sites in Nuits-Saint-Georges.

Climate challenges remain profound, of course. Frost, hail, hydric stress, and disease pressure increasingly dictate the viticulturist’s calendar. But if Clos de la Maréchale teaches us anything, it is that endurance—quiet, steady, and unpretentious—can be its own form of greatness.

A Vineyard That Refuses to Be Forgotten

Ultimately, what makes Clos de la Maréchale so captivating is not its size, its monopole status, or even its long lineage under the Mugnier family. It is the sense that this vineyard, situated just beyond the gravitational pull of Burgundy’s most glamorous names, has persisted through time with integrity.

It asks the drinker and the observer alike to slow down, to pay attention to nuance, to appreciate the subtle architecture of terroir rather than the fireworks. It is a vineyard that rewards those willing to read between the lines.

In a world increasingly defined by speed and spectacle, Clos de la Maréchale stands as a reminder of another way of seeing—one rooted in patience, in history, in geology, and above all, in the enduring belief that greatness does not always need to shout.