Every generation of Burgundy lovers believes, with a certain earnest conviction, that it is witnessing the region at its most profound. Prices rise, domaines ascend, and critics declare new heights achieved. Yet if one wishes to understand Burgundy not as a marketplace but as a cultural organism—rooted in soil, shaped by history, and occasionally misunderstood even by those who claim to admire it—one must travel not to the postwar boom or the Parker era, but back to 1861, when a doctor from Dijon, Jules Lavalle, dared to sketch Burgundy as it truly was.

His book, Histoire et Statistique de la Vigne et des Grands Vins de la Côte d’Or, has slipped into a kind of scholarly mist, cited more often than read. But its importance is impossible to overstate. Lavalle created the first systematic classification of Burgundy’s vineyards, not to flatter the powerful or to stabilise luxury markets, but to give a region in turmoil a clear sense of itself. He looked at Burgundy with both scientific rigour and rural intimacy, and what emerged was a framework so lucid that modern Burgundy still operates within its logic, even when it insists on having outgrown it.

The Burgundy of 1861 was far from idyllic. The Napoleonic Code had fractured estates into impractical fragments; industrialisation was pulling labour away from vineyards; wine fraud and merchant manipulation muddied the reputations of honest growers. Lavalle stepped into this uncertainty with the conviction that clarity must come from the land itself. His hierarchy—Tête de Cuvée, Première Cuvée, Deuxième Cuvée, and Troisième Cuvée—was based not on fashion but on soil, drainage, exposure, and long-term consistency. It was, in many respects, the first modern articulation of terroir.

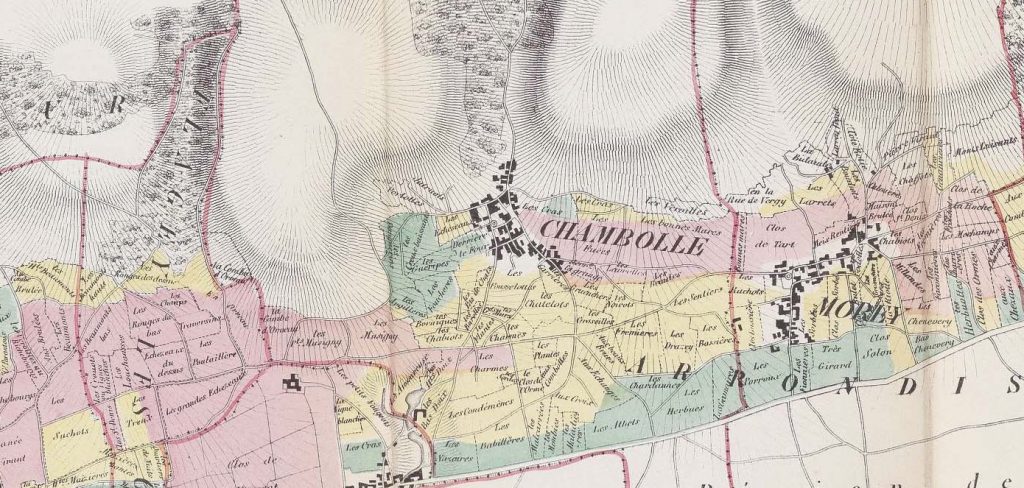

The most striking aspect of his work is how closely his highest tier, the Têtes de Cuvée, aligns with today’s grands crus. Chambertin and Chambertin-Clos de Bèze, Romanée-Conti, La Romanée, La Tâche, Richebourg, and Romanée-Saint-Vivant stood at the summit of the Côte de Nuits. Clos de Vougeot—though only its upper portion—joined them, along with select Corton parcels such as Clos du Roi and Renardes, whose stature he considered unequalled on the hill. In the Côte de Beaune, he placed Montrachet, Bâtard-Montrachet, Chevalier-Montrachet, and Corton-Charlemagne at the pinnacle. To read this list is to recognise immediately that the grands crus of the 1930s were not revolutionary designations at all, but the formalisation of what Lavalle had already concluded more than seventy years earlier.

Yet Lavalle’s restraint is just as revealing. Several vineyards now whispered about by collectors with awe did not make his highest tier. They occupied instead the level just below, the Premières Cuvées—still superb, but not transcendent. Vosne’s Les Malconsorts and Les Suchots, Chambolle’s seductive Les Amoureuses, Gevrey’s Clos Saint-Jacques, Nuits-Saint-Georges’ Les Saint-Georges, Meursault’s crystalline Perrières, and Puligny’s refined Les Pucelles all stood in this second echelon. Lavalle recognised their brilliance, but he also recognised their inconsistency at the time, their susceptibility to imperfections in drainage, frost, or farming. His hierarchy was not a catalogue of modern market darlings, but an agronomic portrait of his era.

We sometimes forget how politically charged this was. By insisting that Burgundy should be understood vineyard by vineyard rather than by amorphous village names, Lavalle challenged the dominance of négociants who profited from ambiguity. His classification stripped away the protective fog that allowed merchants to blend wines freely while selling them under prestigious village labels. To prioritise terroir was, in a sense, an act of rural rebellion—a turning of Burgundy back toward those who worked its soils rather than those who controlled its commerce.

This is partly why Lavalle’s work continues to unsettle modern Burgundy. In a global marketplace saturated with luxury narratives and financial speculation, his classification remains a stubborn reminder that greatness is not determined by price or scarcity. It is determined by land. He worked not from the bottle backward, but from geology upward, evaluating vineyards through their slopes, their exposures, their water retention, their resilience in difficult vintages. His perspective was anchored in agronomy, not aspiration.

If one applied Lavalle’s logic today, Burgundy’s hierarchy might look very different. Some premiers crus that he celebrated—Perrières, Clos Saint-Jacques, Les Saint-Georges, Amoureuses—have long made wines that rival or surpass certain grands crus, and many producers quietly admit that the glass often proves the point. At the same time, some grands crus that enjoy market reverence might not withstand Lavalle’s scrutiny, at least not without uncomfortable questions. Modern Burgundy prefers its hierarchy stable; Lavalle understood it as a living thing.

This is perhaps the most radical aspect of his work: he never intended his classification to be permanent. He believed vineyards evolve. Farming improves or deteriorates. Drainage changes. Vines age. Ownership matters. Climate shifts. For Lavalle, greatness was not a static title but a condition to be re-earned across generations. In this way he was ahead of his time—and ahead of ours.

The true value of his classification lies not in its correctness, but in its integrity. Lavalle evaluated Burgundy before the distorting forces of global fame, astronomical land prices, and speculative collecting reshaped the region’s psychology. He wrote from a moment before Romanée-Conti became a cultural symbol, before Meursault Perrières became a battleground for allocation, before Clos Saint-Jacques became shorthand for insider knowledge. His Burgundy was harder, poorer, more agricultural—but also more transparent. It was a Burgundy that had little choice but to be honest.

And so Lavalle’s 1861 classification endures as Burgundy’s first mirror—still its clearest reflection of what the region is when stripped of glamour and noise. The question today is not whether Lavalle got every ranking right. It is whether modern Burgundy has the courage to revisit the clarity of his approach, to accept that the land, and not the market, is the true arbiter of greatness.